Background

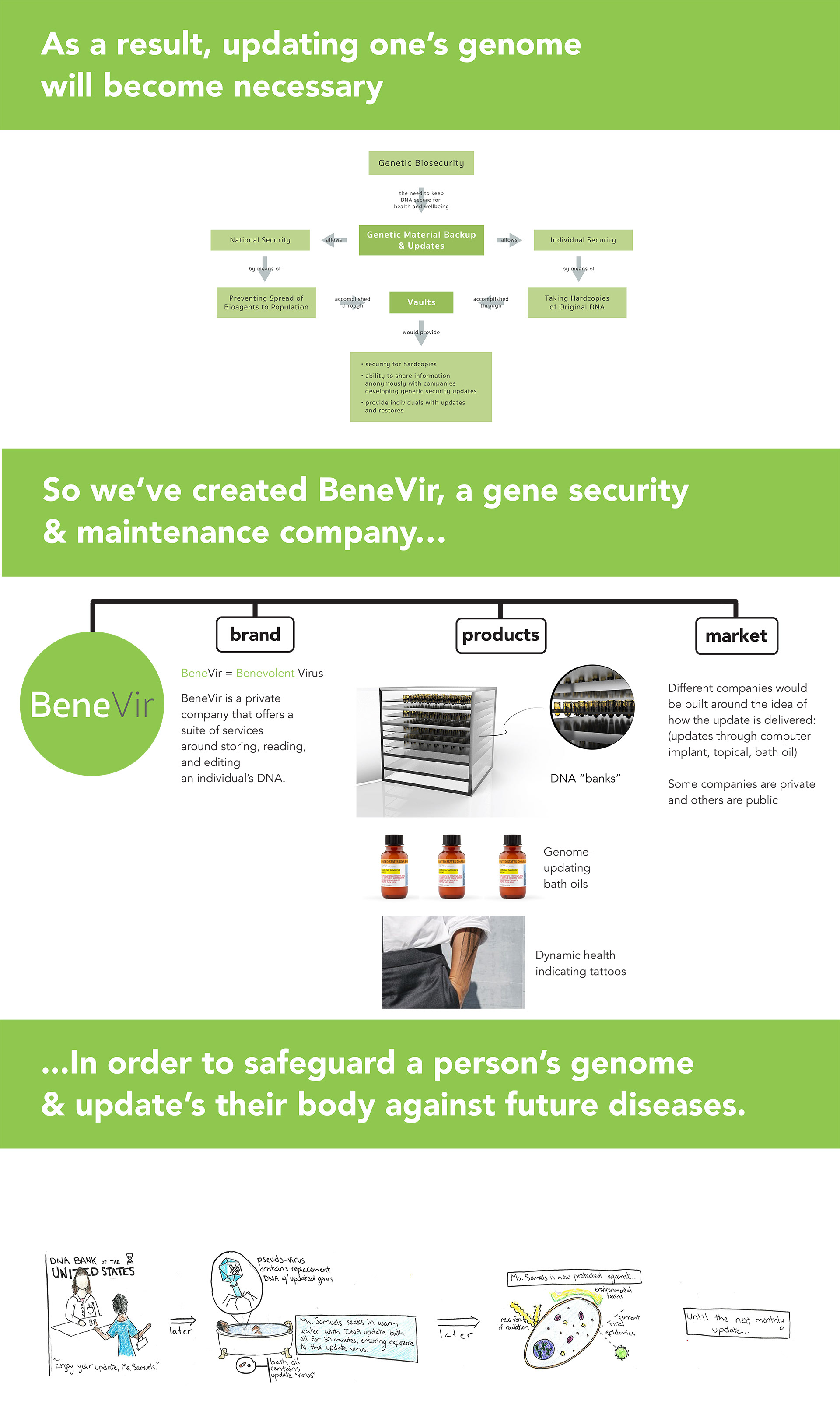

People commonly protect their cybersecurity on an individual level by backing up their data and installing security updates on a regular basis; a similar system is possible for biosecurity. BeneVir is a speculative biosecurity company; the name is a portmanteau of “benevolent virus”, as the genetic updates will be implanted into cells using engineered, neutral viruses (an extrapolation of current gene therapy research methods). BeneVir customers submit DNA samples to the company, which copies each person’s genome and stores it in a high-security vault as a physical sample. The company identifies a unique, inert “tag” in each genetic sequence, which functions as an IP address or Social Security Number for the customer. Customers can then choose to get a biosecurity-monitoring tattoo, which remains invisible until the cells within it are infected with a new DNA sequence that does not contain the gene tag, causing it to change color.

BeneVir releases genetic updates at regular intervals, usually biannually, but sometimes in response to current events. These genetic updates can be picked up at the customer’s local pharmacy, and contain protections against harmful forms of radiation (many forms of radiation that have unknown effects today are definitively linked to cancer in the future), environmental toxins (usually chemicals that industry lobbyists wish to continue using), and current epidemics and engineered biothreats. Customers are also encouraged to regularly back up their DNA, usually also biannually.

Research

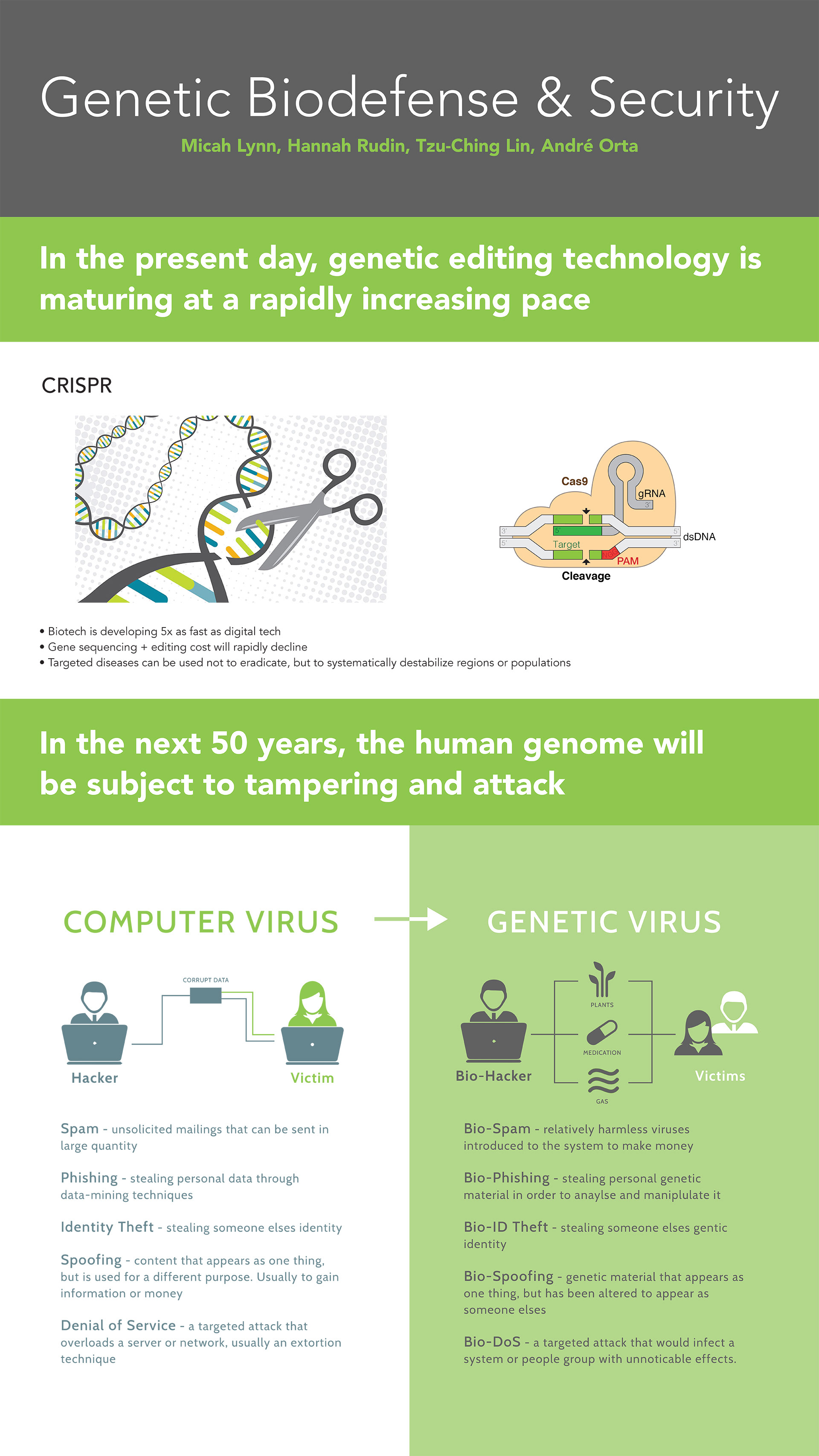

Advancements in gene technology are hitting the world in big ways. The Crispr-Cas9 machine can not only sequence a genome, but also can cut and splice sections of DNA. While computer technology has been approximately doubling in processing capability and speed every two years (tracking with Moore’s Law), gene technology is advancing at five times that rate. Fewer than fifty years into the future, gene-editing devices may be as ubiquitous and affordable as laptops.

In order to be prepared for the darker consequences of this sort of progress, one can continue this comparison with computer technology; malware, spam, and denial of service are all examples of cyber attacks that have genetic parallels. Denial of service (DoS) attacks, for example, are a type of cybercrime that can cause large-scale economic damage with minimal permanent damage to code or infrastructure (see the DoS attacks that hit major US banks in September 2012). The biological analog of this type of attack might be an engineered virus that simply causes lethargy or a slower metabolism for anyone infected in a region, slowing commerce and increasing health costs with minimal damage to people or infrastructure.

This future system resembles the current health insurance landscape, where better health insurance results in better coverage. However, costs for buyers are greatly reduced by the intercompany trade of data and research – information is secure, but not necessarily private.

Process

The first step for this project was to characterize the current states of things: we researched biosecurity, biowarfare, genetic technology, and the current speculations of experts. After reading an article co-authored by biotech expert Andrew Hessel that compared future biosecurity threats to current cybersecurity threats, we were inspired to adopt and expand upon that framing of the future state. As such, we researched current cybersecurity threats, motives for attacks, and societal responses. We also looked into gene therapy, how viruses work, bionics, agricultural risks, current seed and DNA vaults, vaccines, and more.

This broad and deep research helped us develop an informed foundation from which to have interesting speculative brainstorm sessions. We had a very clear framing statement and system map, so our initial product brainstorm yielded four concepts that complimented each other; Richard Tyson, one of our instructors, urged us to carry all four of them forward into our final presentation under the business umbrella of a speculative biosecurity company that he called “BeneVir” (off the top of his head!). Our final tasks were to develop a cohesive presentation, which we accomplished by telling a story through our poster and by using physical prototypes to immerse the critics into our future world.

Credits

This project was done in collaboration with Tzu-Ching Lin, Micah Lynn, and André Orta.

Full credit to Richard Tyson for the name BeneVir and idea to compile our concepts as a company. James Wynn, our other instructor, also provided influential critiques throughout the process.

“The Biocrime Prophecy”, an article co-authored by Mark Goodman and Andrew Hessel for Wired, was one of the most pivotal research articles for this project, as it introduced the parallels between cybercrime and future biocrime.